Reversing the PISA decline: national challenge requires national response

Research 6 Dec 2016 8 minute readGeoff Masters describes the macro- and micro-reforms that are likely to lead to improved student learning, and better performance in international assessments of science, maths and reading.

The past week has seen the release of results on the performances of Australian school students from two major international surveys – the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS 2015) and the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA 2015) – as well as the National Assessment Program, Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN 2016).

While these results reveal some improvements in reading and numeracy levels in primary schools since 2008, especially in Queensland and Western Australia, in secondary schools, achievement levels have at best stagnated.

As we saw last week, TIMSS has shown that there has been no improvement in Year 8 mathematics and science since 1995. Over this period, achievement levels in a number of other countries (including England, the United States and Singapore) improved, resulting in some countries overtaking Australia.

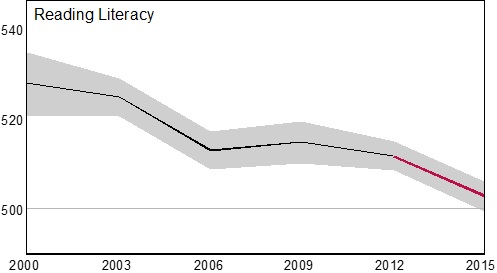

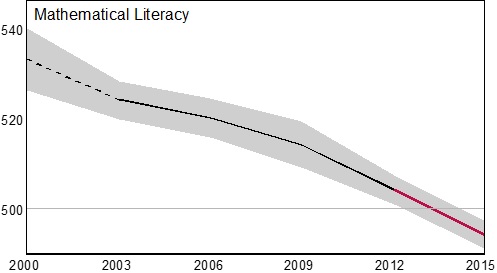

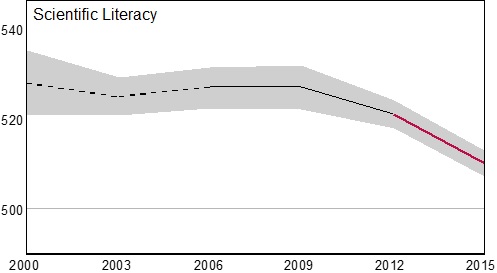

Today’s PISA evidence is more concerning. PISA assesses 15-year-olds’ abilities to apply higher order skills and thinking in real world contexts – referred to by the OECD as reading literacy, mathematical literacy and scientific literacy. Australian students’ abilities to apply higher order skills and thinking have been on a steady decline since 2000, as the following graphs show. In 2000, Australian 15-year-olds performed well above the OECD average (set at 500). By 2015, this was no longer the case despite the OECD average itself dropping below 500. In mathematical literacy, which became a major assessment domain in 2003, the decline was dramatic.

Over the past two decades, there has been no higher priority in Australian school education than raising students’ literacy and numeracy levels. The introduction of state and national literacy and numeracy tests, the publication of NAPLAN results on the My School website and national partnership funding focused on literacy and numeracy have been among many government initiatives designed to lift levels of student performance in these fundamental skill areas. Despite the high priority given to literacy and numeracy, the recently released PISA, TIMSS and NAPLAN results show no improvements in secondary schools. And there is no obvious reason to expect improvement in the future.

So what will it take to lift achievement levels in Australian schools?

One thing we know with certainty is that levels of student achievement are influenced by the quality of teaching. Any lift in performance will depend on changes in classroom practice in schools throughout the country. This in turn will depend on teachers who are knowledgeable about the subjects they teach, who have the diagnostic skills to analyse learning difficulties and who are able to implement highly effective teaching interventions.

Part of the long-term solution is to increase the capacity of the Australian teaching workforce. High-performing countries have been remarkably successful in raising the status of teaching and attracting highly able people into teaching. At present, Australia is heading in the opposite direction; fewer of our most able school leavers are choosing teaching as a career and this is further lowering the status of teaching. We must break this cycle. Higher order skills and deep understandings of subject matter depend on highly knowledgeable teachers. We must learn from international experience and make it a national priority to increase the number of highly able young people choosing to become teachers.

Another part of the solution is to support improved teaching in current classrooms. Three broad kinds of support for teachers are likely to lead to improved student learning.

- Clear maps of the long-term development of knowledge, skills and understandings in learning areas such as reading, mathematics and science.

Many students fall behind in their learning because their current levels of achievement and learning needs are not well diagnosed and addressed. Many teachers are focused instead on delivering the curriculum for a particular year of school and then assessing and grading all students on how well they have learnt what has been delivered. Under this approach, there is often little incentive to establish exactly where individuals are in their long-term progress.

Establishing where students are in their learning is essential for targeting teaching and maximising learning. In any year of school, the most advanced 10 per cent of students are typically five to six years ahead of the least advanced 10 per cent of students. When teachers deliver the same year-level curriculum to all students regardless of their current levels of attainment, less advanced students sometimes struggle and fall further behind, and some more advanced students are unchallenged and learn less than they might.

To identify where individuals are in their learning and to target teaching accordingly, teachers require a map that describes long-term (multi-year) progress in an area of learning – that is, a description of how knowledge, skills and understandings develop over an extended period of time. School curricula commonly incorporate such learning progressions, but often with the accompanying expectation that teachers will assess and grade all students against the same year-level expectations.

Large-scale improvement depends on teachers using well-mapped learning progressions to pinpoint where individuals are in their progress, set personalised stretch targets for further learning and share information about progress over time with students and parents.

- Classroom resources to assist teachers in their diagnosis of student learning.

When the focus of assessment in schools is on grading all students against common year-level expectations, many less advanced students receive low grades year after year. Some conclude that they are poor learners and eventually disengage. More advanced students generally receive high grades, but sometimes with minimal effort or annual growth.

The alternative, and the approach required for improvement, is to focus assessment on establishing and understanding where individuals are in their learning – that is, on what they know, understand and can do at the time of assessment. For teaching and learning purposes, this needs to be done with a degree of diagnostic precision; for example, identifying errors that students are making or misunderstandings they have developed. The purpose is to establish starting points for teaching and to identify the need for specific teaching interventions.

In learning areas such as mathematics, science and reading, teachers generally benefit from access to quality resources that assist them in answering such questions as: Where is this student up to in his or her learning? What specific difficulties are they experiencing? What progress have they made? But in many schools, assessment resources of this kind are either not available or not used. The focus instead is on assessing students against common year-level expectations. This is a particular issue in many secondary schools.

- Access to proven, evidence-based teaching strategies and interventions.

Coherent learning progressions that make explicit how knowledge, skills and understandings develop over time and quality diagnostic resources that teachers can use to establish where individuals are in their learning need to be accompanied by clear, evidence-based teaching strategies. Having established where individuals are in their learning – including their knowledge gaps, errors and misunderstandings – teachers require proven teaching interventions to address specific difficulties and promote further learning.

Too often, the onus is on teachers to decide what teaching strategies are likely to be effective. They are expected to learn on the job and to create their own interventions. But this expectation seriously underestimates what is known from experience and research about more and less effective teaching practices. It undervalues the knowledge base of the teaching profession.

Wide-scale improvement in Australian schools depends on promoting evidence-based teaching practices in all schools. Often these practices will include explicit teaching of curriculum content. In some situations, teachers will benefit from clarity about the steps they should follow in addressing specific student difficulties or skill gaps. Recommended interventions of these kinds will not undermine the professionalism of teachers – as is sometimes feared – but are an important step in acknowledging the existence of a growing professional knowledge base.

The recently released PISA, TIMSS and NAPLAN results identify a national challenge that requires a national response. There are macro-reforms that governments can make to improve the long-term quality of teachers and teaching. There are also immediate steps that governments can take to promote micro-reforms that will lead to improved literacy, numeracy and science teaching and learning in Australian schools.

Read the full report:

PISA 2015: A first look at Australia’s results, by Sue Thomson, Lisa De Bortoli, Catherine Underwood, ACER (2016).