Growth and ‘quality’ in higher education

Research 16 Jan 2014 5 minute readStrong growth in university enrolments may not necessarily be affecting quality, according to analysis by Daniel Edwards and Ali Radloff.

Growth and 'quality' in higher education

Recent expansion in Australian higher education has been driven by three key policies: demand-driven funding for students in public universities; a target of 40 per cent of 25- to 34-year olds attaining a bachelor degree or above by 2025; and a target of 20 per cent of undergraduate enrolments to be from low socioeconomic backgrounds by 2020.

The strong growth in university enrolments in recent years raises questions as to the extent to which quality may be compromised. While there is an absence of strong data to address the impact of growth on quality, measures like the Australian Tertiary Admissions Rank (ATAR) and attrition can serve as proxies to investigate whether there is any relationship between growth and quality in higher education.

The ATAR as a measure of quality

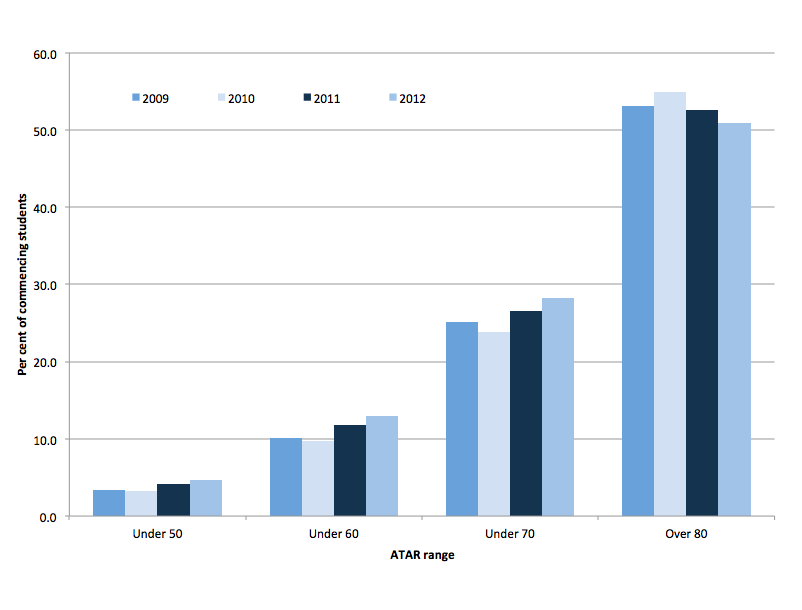

Data for university enrolments show that overall commencement numbers increased by 16.7 per cent between 2009 and 2012. Figure 1 explores how the ATAR distribution of commencers changed during this growth period, On average, change on this measure has been marginal. The share of commencements for students with ATARs under 50 grew very slightly from 3.1 per cent to 4.2 per cent, for all commencers with an ATAR under 60 from 9.7 per cent to 12.3 per cent and for all commencers with an ATAR under 70 from 24.6 per cent to 27.4 per cent. As a result, there was a slight decrease in the proportion of all commencers who had an ATAR above 80 – from 53.8 per cent in 2009 to 51.7 per cent in 2012.

Figure 1: ATAR distributions for domestic undergraduate commencers 2009 to 2012, all publicly funded universities

Since the ATAR is essentially a percentile rank of a given age cohort, it is inevitable that as more applicants enter the system the overall spread of the ATAR will trend downwards. What this big picture data shows, however, is that even in a period where enrolment growth has been substantial, the impact on ATAR scores across publicly funded universities as a whole has been relatively small.

Looking at the six highest growth universities, which have each seen enrolment growth in excess of 40 per cent from 2009 to 2012, the percentage point change in ATAR distribution has been slightly larger than for the sector as a whole, but the differences were not found among the lowest ATAR grouping – the proportion of commencers with an ATAR under 50 increased by only one percentage point. Where the change is different to the national trend is in the students with an ATAR of 60 or below, where the increase was from 11.9 per cent in 2009 to 16.3 per cent in 2012, while the increase for those with an ATAR under 70 was from 31.6 to 38.9 per cent.

While there is some evidence to show a change in ATAR scores in the cohorts entering the fastest growing institutions, this change is not occurring rapidly among the very low ATAR students and it is difficult to determine the extent to which this change suggests any noticeable diminishing of quality across the system or in the high-growth universities.

Attrition as a measure of quality

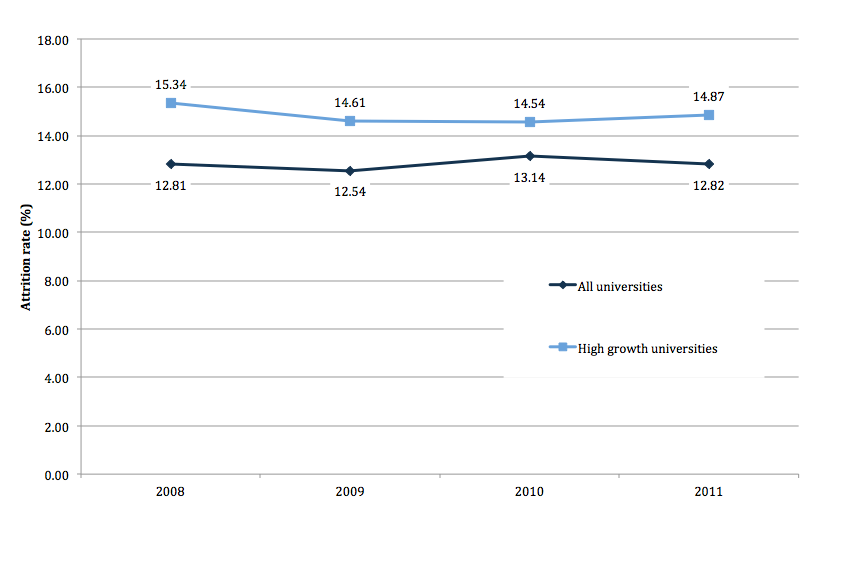

Another way to explore the impact of growth on quality of provision in publicly funded universities is through attrition rates – that is, the extent to which students do not progress through their first year of university. As Figure 2 shows, between 2008 and 2012 there has been only small movement in attrition rates among all publicly funded universities and, while slightly higher among the high-growth institutions, attrition remained relatively stable during the large period of growth from 2009 onwards.

Figure 2: Attrition rates of commencing student in first year of university, all publicly funded universities and six high-growth universities, 2008 to 2012

These findings using the ATAR and attrition as proxies suggest that the impact of growth in higher education institutions has not had any significant influence on quality in terms of achievement prior to entry or on the likelihood of completing first year.

Meeting the low socioeconomic status target

The growth of higher education enrolments in the past few years has been greater among those from areas of low socioeconomic status (SES) than it has been for other students. Low SES commencements grew by 29 per cent from 2009 to 2012, at twice the rate at which commencements from the highest SES quartile grew and at a faster rate than the national average of 21.3 per cent.

While this increase is good news, the proportion of all commencers who are from low-SES backgrounds increased from 16.9 per cent in 2009 to 18.0 per cent in 2012, a small gain of 1.1 percentage points. Looking at all enrolments, the gain over this period of massive growth was more marginal, from 16.1 per cent in 2009 to 16.9 per cent in 2012.

It would seem that gaining the remaining 3.1 percentage points to reach the 20 per cent target in the space of seven years seems to be unrealistic if the status quo is maintained.

One way to increase the chances of expanding low-SES participation may be by extending Commonwealth-supported places to private providers and TAFEs. While these providers currently enrol a lower proportion of low-SES students than do publicly funded universities, this may be because of upfront fees. The modes of provision supported by many private providers in terms of relatively small class sizes and often a more pastoral approach to teaching and learning may be attractive to low-SES students seeking to participate in higher education.

Read the full report:

This article draws on ‘Higher Education enrolment growth, change and the role of Private HEPs,’ a background paper prepared by Daniel Edwards and Ali Radloff for the Australian Council for Private Education and Training (ACPET).