Promoting cross-border education – Student mobility

Research 4 Dec 2014 6 minute readIn this four-part series, Sarah Richardson and Ali Radloff highlight the key considerations for strengthening collaboration around cross-border education. Here they address the movement of students from one country to another.

Promoting cross-border education – Student mobility

Universities have long played a significant role in educating the next generation of professionals, driving innovations in research and shaping national debates. But gone are the days when universities have been able to focus solely on their national contexts.

Cross-border education is a topic of considerable importance to Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) economies, contributing directly to APEC's goal of supporting sustainable economic growth and prosperity in the region.

Two key goals of cross-border education are to enhance the quality of education available to students and to stimulate innovation in research to solve global dilemmas. Both of these call for a high degree of integration between universities in different countries across four key areas:

- student mobility

- researcher mobility

- provider mobility, and

- virtual mobility.

Student mobility patterns

The movement of students across international borders is arguably the most visible aspect of cross-border education.

According to the OECD’s Education at a Glance series, in 2011 there were 4.3 million internationally mobile students – nearly double the number a decade earlier.

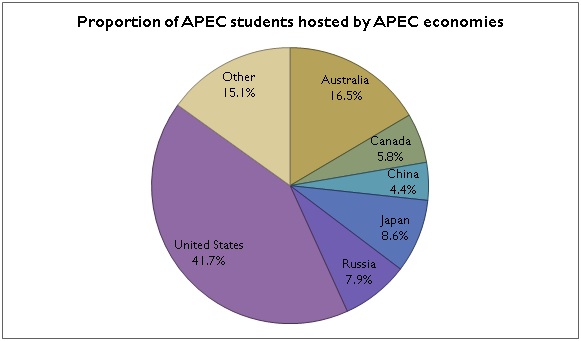

Figure 1 shows the proportion of APEC students hosted by APEC economies, based on UNESCO’s Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students report.

Source: http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Pages/international-student-flow-viz.aspx (link unavailable) UNESCO (2013) Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students

The most popular destinations for students from APEC economies are the United States and Australia, reflecting the importance of the English language in decisions about international study. Beyond language, intra-regional mobility is important. For example, intra-regional mobility influences the flow of international students to Japan from China, Korea, Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia.

Among APEC communities the two most predominant types of student mobility are ‘degree mobility’, when a student moves abroad to undertake a whole degree or qualification, and ‘credit mobility’, when a student moves abroad for part of their qualification.

Although the absolute numbers of degree-mobile students from APEC communities is large, their number as a proportion of the tertiary population is relatively small, indicating significant potential for growth in future years.

As the number of internationally mobile students continues to grow, understanding the patterns and drivers of student mobility will be increasingly important, as will be understanding the way in which international mobility impact students’ attitudes, and academic and career outcomes. The development of a shared data collection on the patterns, outcomes and impact of student mobility is vital.

Barriers to student mobility

Language

Language of instruction is one of the main influences on internationally mobile students’ decision on where to study. The dominance of English-language instruction in many countries may limit the international mobility of non-English speaking students. Language barriers also affect internationally mobile students’ experience of study. Support to help mobile students cope with a lack of proficiency in the language of instruction would go a long way to helping make international study more attractive for those with less confidence in their language skills.

Cost

Several studies have shown that students from disadvantaged backgrounds are under-represented among internationally mobile students. For example, the 2012 Australasian Survey of Student Engagement found that, by later years of study, only four per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students from Australia have studied abroad compared with nine per cent of non-Indigenous Australian students. Supporting the mobility of disadvantaged students is essential.

While most APEC economies have well-established scholarship schemes available for international students, due to the diversity of groups offering the scholarships it can be difficult for students to find eligibility information. Development of a central repository of information on scholarships to support mobility would help overcome this problem.

Learning outcomes and credit transfer

Developing smooth credit transfer systems encourages participation in short-term study abroad schemes and helps facilitate the credit mobility of students. Although there are currently no global credit transfer systems, some regional systems have been implemented. Regardless of the availability and quality of frameworks for credit transfer, however, they cannot automatically guarantee that students have achieved the skills and knowledge defined in a course or degree.

Collecting evidence on student achievement of learning outcomes requires shared assessment practices. The OECD’s Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes Feasibility Study demonstrated that it is possible to compare learning outcomes internationally. Further development of shared qualifications frameworks and assessment collaborations in key disciplines would yield a number of benefits for cross-border education.

Immigration policies

While access to work opportunities and immigration policies are important factors in enticing students to study abroad, restrictive or overly bureaucratic visa conditions on immigration can negatively impact on students’ international mobility. Difficulties in understanding visa requirements, high application costs and fees, and lengthy waits for approvals may deter prospective international students, while restrictions on working may impact on students’ access to practicum or work experience opportunities related to their study. The development of a central repository of visa requirements for study would go some way to addressing these issues.

Strengthening collaboration

Today’s graduates can be expected to work in all corners of the world, and the need to be ready for this puts pressure on universities to ensure that curricula and teaching enable students to gain appropriate skills and knowledge.

Despite the benefits of cross-border education, universities and governments can be cautious about engaging, fearing that these benefits will come at the expense of their ability to protect national interests and respond to local demands; however, carefully thought out collaboration will enable the expansion of cross border education in ways which are of benefit to all economies.

Further information:

This article is based on the discussion paper ‘Promoting Regional Education Services Integration’, prepared ACER Principal Research Fellow Dr Sarah Richardson and ACER Research Fellow Ali Radloff to inform the APEC University Associations Cross-Border Education Cooperation workshop held in Kuala Lumpur in May 2014, and the subsequent workshop report, published by APEC in September 2014.